The empty child

Hello. Might seem like a stupid question, but has anything fallen from the sky recently?

This seemed tough. When I started writing this weblog, I made a decision to write one post per episode, not per story. It looked like it was rather difficult to say anything about The empty child without getting into the territory of The Doctor dances, which I will cover in two weeks. (And by the way, if you’re reading this, and if you want to read my thoughts past Series 1 with a reasonable frequency, consider supporting me in one way or another. Sadly, as of now the support I get is way below the threshold needed for this weblog to continue at the pace of one post per two weeks after I get to Ten…)

Are you my mummy?

It turned out, however, that there are quite a few things that can be said about The empty child even though it ends with a cliffhanger and I’m not allowed (by myself, of course) to reveal too much. Please note, however, that – according to my own policy – I avoid spoilers, so I may deliberately mislead you in certain aspects of this episode, much like the story itself.

Who is Nancy?

Quite obviously, Nancy is one of the central characters here. (That despite Captain Jack Harkness doing his best to steal the spotlight.) I admit that she is one of my favorite characters of the whole series. This episode poses an important question, though. Is her choice to enter empty houses during air raids and feeding homeless children with the food gathered there a right one?

Now that’s not necessarily an easy question. The situation is far from “normal” (whatever that means). She clearly does not seek personal gain, and despite her young age, she is an obvious motherly figure for those poor kids. Not only does she feed them, she genuinely cares for them and also does her best to teach them restraint (“one slice each”!) and good table manners. And it seems that the family whose dinner she took and then gave to the children got it in a not-fully-legal way anyway.

She’s still entering other people’s houses and taking their property, though. Such an action may be morally justified in extreme circumstances (people dying of hunger, for example). However, these children – even if malnourished – are not literally starving. (One of the boys mentions how “it’s better on the streets anyway. It’s better food”. So they were fed even without Nancy, just with cheaper stuff.) Even if Nancy is definitely not the villain of this story (this distinction really goes to Captain Jack!), despite how much I sympathize with her – I have to say that no, she didn’t choose well. (Mind you, given the trauma she went through, her young age and the resulting inexperience, I wouldn’t dare to say that she actually bears full blame for her bad choice, but that’s another question.)

This, by the way, makes me somewhat sad. If she were saving these children from starvation, it would make for a way more interesting problem, and I love when a work of fiction poses such an issue. It would be sort of a “moral playground”, where you can ponder difficult ethical choices without having to choose for real and face possibly bad consequences. Also, such a story would be a great example why it is impossible to “codify” morality as a (perhaps very long) list of things you must or must not do, eliminating the need of personal judgement. You need some general rules (like the Ten Commandments), but then you also need a rational person with a well-formed conscience to be able to apply these rules to a particular situation. To continue the example of taking someone else’s food when you are starving, the Catechism of the Catholic Church says (CCC 2408):

There is no theft […] in obvious and urgent necessity when the only way to provide for immediate, essential needs (food, shelter, clothing…) is to put at one’s disposal and use the property of others.

Some people might think that the Catechism is exactly that – a long list of things you must or must not believe and do – and it sort of is – but it’s still not comprehensive, because it can’t be. Notice how the ellipsis suggests that “food, shelter, clothing” are just examples, not an exhaustive list. If Nancy were taking care of a traumatized 4-year-old child who witnessed death of their parents, would a toy be an “obvious and urgent necessity”? I can easily imagine arguing that yes, it would – but on the other hand taking a small child’s toy seems much more cruel than just taking someone’s dinner… So if anyone hoped for a full and easy to follow instruction on how to live your life well without thinking and making moral decisions – well, you won’t find it. And, to (mis)quote the Man in Black, “anyone who says differently is selling something”. ;-)

What I like even less is that the actual script is very quick to praise Nancy’s actions (“It's brilliant. Not sure if it's Marxism in action or a West End musical”). In fact, this is a very strange remark from the Doctor – he utters the words “Marxism in action” like a high praise. Well, I was born and raised in one of the places in Europe where Marxism actually was being applied to govern the country. To say that it sucks is a gross understatement. The amount of suffering and death Marxism (and its descendants) caused is unimaginable. To hear the Doctor using this very word as a praise is almost physically painful for me… Besides, I think that the episode would be much better if the actual judgment of Nancy’s actions was left ambiguous as something for the viewers to wrestle with.

Hello, I’m Nancy. Stealing doesn’t bother me, but bad table manners do. I might become a doctor in the future…

Let’s move on. There are two more things about Nancy which are truly powerful. One is how she is depicted as someone who lived through a trauma, and how she reacts to the Empty Child being nearby. spoiler for series 1It is of course especially heartbreaking on a rewatch, when you already know the plot twist from The Doctor dances. One outstanding moment is when she speaks with the Doctor in the house while the Empty Child is standing right outside the door. You can see how unsettling it is for her, and when she hears the boy say “mummy” in his creepy tone for the umpteenth time, she snaps, tells the Doctor, “you stay here if you want to”, and runs. Poor Nancy… And what I appreciate even more is how the Doctor instantly understands her, asking her a truly armor-piercing question, “who did you lose?”. It is quite clear that Nancy blames herself for the death of her little brother, and said brother becoming basically a zombie and harassing her doesn’t help a bit. Trying to “make up” for her apparent “fault” by helping other children seems a very natural reaction, but that doesn’t make it any less tragic. Frankly, I think the only reason Nancy didn’t get a good hug in this episode was that Nine is not exactly a hugging type, and Rose was elsewhere at the time. (Not that a hug would help a lot – but it might help a tiny bit. Hugs are great, and I’m certainly not against the hugging.)

But there is one more scene with Nancy which resonates with me a lot. When the Doctor follows her and she is astonished that he was able to do that (“people can’t usually follow me if I don’t want them to”), he quips that he’s “got the nose for it”, since “[his] nose has special powers”. And what happens next? Of all things, Nancy asks him if his “ears have special powers too”, with a mischievous smile! This scene never fails to amaze me. Here we have a young lady, in the middle of a war, living in a severe trauma – and she is making fun of a strange man with big ears. This human ability to distance oneself from the most severe circumstances, make jokes and laugh, has fascinated me for years. Undoubtedly, it is some kind of psychological coping mechanism, but just think about it. In extreme situations, people can act with selfless love or unbelievable heroism. These are the big words. But in such moments, people also are capable of retaining the little brother of those grand qualities – their sense of humor. This is so beautiful it almost makes me cry.

The Doctor and children

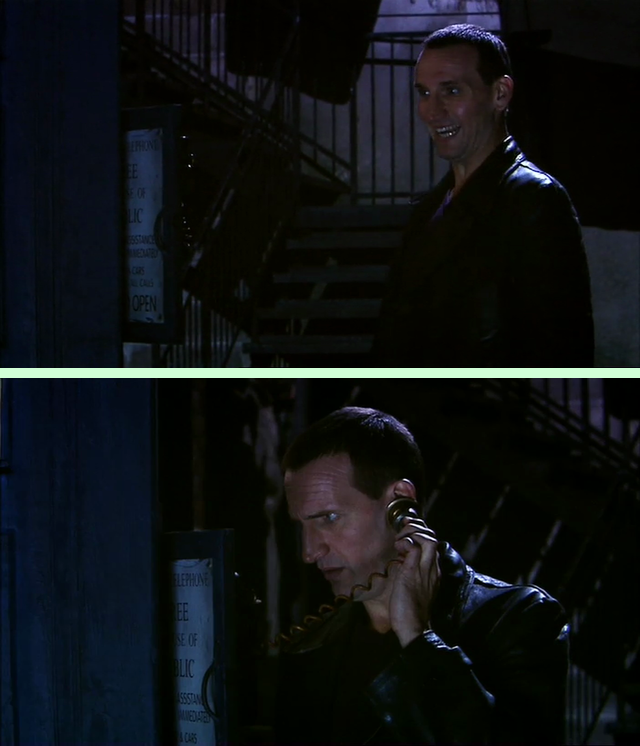

I think this is the first time in New Who – and probably the only time for Nine – when we watch the Doctor interact with children. Different incarnations have slightly different attitudes, of course, but he is generally known to like and take care of them. (Eleven will turn it up, well, to eleven.) And how he handles them is brilliant. Him joking with the children Nancy was feeding was incredibly cute. He must have been aware that they were in a terrible psychical shape, and spoiler for series 7seeing children in the midst of war must have triggered an enormous guilt inside him, but he still managed a smile and a few jokes. (And speaking of terrible psychical shape, one of the boys suggests he was abused sexually, which makes one shudder.) And the epitome of the Doctor being especially protective towards kids is his attitude to the Empty Child. We can see it first when he answers the T.A.R.D.I.S.’ phone. He is clearly enjoying himself. “A phone that isn’t a phone gets a phone call” – and that is right after he claimed that there is basically nothing in the universe that can surprise him. How not to be thrilled? He is literally grinning when he answers the call – and then he hears a frightened child, and his grin fades away in a second. This is what I call great acting (and great storytelling, too, by the way). It is amazing how much meaning Chris Eccleston could convey in these two seconds, without even saying a word. And then, less than ten minutes later, the Doctor tells Nancy, “it’s never easy being the only child left out in the cold”, and when she calls him out (“I suppose you’d know”), he says – with that clownish smile of him – “I do, actually, yes”. Just thinking what he must have experienced as a child (we will get some very short glimpse in spoiler for series 2The girl in the fireplace, spoiler for series 3another bit in The sound of drums spoiler for series 8and then much later in Listen) gives me shivers. And seeing this smirk of him makes me want to run and hide. (If that’s not what you feel, consider that this is the same smile he was wearing when talking to the Dalek in van Statten’s vault, and he’ll put the same mask spoiler for series 1during the “date” with Blon Fel Fotch and again while speaking with the Daleks in Bad Wolf.

Top: A phone that isn’t a phone gets a phone call, how cool is that? Bottom: oops, there’s a child in trouble.

Captain Jack Harkness

Any discussion of The empty child would be incomplete without mentioning Captain Jack Harkness. I have to admit that I have rather mixed feelings about him. On the one hand, he is a very likable person, with his laid-back attitude to life and great sense of humor. On the other hand, he tends to have a very… specific attitude to people, especially people who he considers attractive. Let’s just say that it’s hard to treat him as a role model for people who consider that certain behaviors are only appropriate between a husband and a wife and leave it at that. Add to that his general carelessness and it’s not hard to understand why I’m not a fan of him.

That said, I like the way his character was introduced as someone who was also not from this time and place. Him asking Rose to “switch off her cell phone” was a nice way to show her – and us – that she and the Doctor are not the only time travellers here.

On the other hand, I am a bit on the fence with the latter part of Jack’s introductory scene. His flirting with Rose (and Rose’s with him, let’s be honest) was really funny and maybe even cute, but come on. I know that Rose is not married, but I felt bad for poor Mickey. Despite all his faults, he at least deserved to be told clearly that he should not consider Rose his girlfriend anymore at least four episodes ago. The interactions between Rose and Captain Jack, however, are a great (even if sad) example of how people often behave. Let’s cheat for a moment and treat Rose and the Doctor as the “official” couple. The dynamics of their interactions are so common. The Doctor, the older and more mature one, is someone who may not be the most “fun” to be with (after all, he didn’t “give Rose some Spock” despite her requests), but is reliable and serious in his commitment. And Rose, the younger and immature one, who basically gets infatuated with a new man every other episode. First there’s Adam, then the whole situation with Pete (whose relationship with Rose was obviously very different in nature, but she still basically ignored the Doctor and his warnings), and now Jack. It is as if the writers wanted to show us the better side of Rose in the first five episodes, and now decided that we should learn that she’s not really that good a person. I’m all for realistic, multi-dimensional characters, but Rose in the latter half of Series 1 moved from “flawed” to “almost unbearable” pretty quickly. (As a side note, this dynamic between a more stable (even if far from perfect) man and a more irresponsible girl seems surprisingly common in New Who. Rose and Mickey, Rose and the Doctor, spoiler for series 5Amy and Rory, spoiler for series 8Danny and Clara… Interestingly, examples of a reverse situation seem to be more rare, even if they are pretty common in real life.

My name is Rose, my official boyfriend is 64 years away, my new kind-of-boyfriend doesn’t see me, a handsome stranger wants to dance with me on an invisible spaceship tethered up to Big Ben during a German air raid, and I’m absolutely fine with that.

Let’s get back to Captain Jack Harkness, though – I have one more thing to say about him in this episode. The scene near the end when the Doctor is furious at him, assuming the whole gas-mask-zombie plague was somehow started because of the “Chula warship” crashing in 1941 London, is really great. Watching the Doctor being angry at someone is always fascinating, and as we will see, Nine’s anger looks completely different than Ten’s or Eleven’s one. (To be honest, if I had to choose which incarnation of the Doctor I’d prefer to be around when he’s angry, I’d choose Nine over Ten and Ten over Eleven without a second thought, by the way. Angry Ten is really scary, and angry Eleven is downright terrifying. But let’s not get ahead too much.)

Other tidbits

As usual, there are some smaller details I’d like to just point out without much analysis. For example, I like the opening scene of the episode, when the Doctor tells Rose the meaning of “muave” and “red”. It’s really a pity that it wasn’t referenced later in any way. For example, in spoiler for series 4Voyage of the damned the PA system can be heard announcing “red alert”. I am aware that saying “muave alert” would be confusing especially to casual viewers (who were supposed to be a significant part of the audience of that episode), but I still consider this a bit of a lost opportunity.

Mauve, the universally recognized color for danger

On the other hand, if you look closely, it is the Albion Hospital (again!) where something strange and alien happens – this is a great callback to Aliens of London.

Anyone knowing classic Who must have been very excited to hear the Doctor’s reaction (“Yeah, I know the feeling.”) to doctor Constantine saying “before this war began, I was a father and a grandfather. Now I am neither. But I’m still a doctor”. This is another fantastic reference. (Though technically, even if his children and grandchildren are dead, he still is a father and a grandfather, of course.)

Another great piece of trivia is where the name Chula came from. When I was watching one of the special features on one of my Series 1 DVDs, there was this moment when Steven Moffat (who wrote The empty child and The Doctor dances), Paul Cornell (who wrote Father’s day), Rob Shearman (who wrote Dalek) and Mark Gatiss (who wrote The unquiet dead) were sitting and talking in a restaurant called “Chula”. Wow. So this is where they get these alien names from!

When the Doctor accused Rose of “strolling”, her answer was this: “Who’s strolling? I went by barrage balloon. Only way to see an air raid”. That was really funny! And so was the absolutely priceless look on the Doctor’s face after Jack’s comment on his outfit (“Flag Girl was bad enough, but U-Boat Captain?”), too.

The next detail I’d like to point out in this section is yet another easy to miss line. When Nancy evacuates the children from the Lloyds’ house after the Empty Child turns up, one little girl – maybe six, maybe seven years old – sits stupefied and can’t move. Nancy telling the little kid that it’s like a chasing game made it truly heartbreaking… As a father of two I almost couldn’t watch that scene without a tear in my eye.

And finally, there is a short (about 5 minutes) documentary about the filming of the barrage balloons. They considered doing them as CGI, but settled for miniatures instead – hence its hilarious title, Mike Tucker’s Mocks of Balloons. (Mike Tucker was the model unit director, and the bulk of the documentary was him being interviewed. Funnily enough, another person interviewed was a cameraman called Peter Tyler.)

Last but not least

There is one more tiny detail in this episode which I consider very touching and deeply true, and it doesn’t have to do anything with Nancy. We have two pairs of people here which are in stark contrast to one another. On the one hand, there’s Jack, which is obviously flirting with Rose (not that she has much against it!), but – charming as he is – he is completely irresponsible. Dancing on a spaceship parked near the Big Ben in the middle of WW2 air raid? Seriously? Not to mention the whole Chula ship thing. And on the other hand, we have Mr and Mrs Lloyd, whose marriage (spoiler for series 1as we will see especially in the next episode) is quite obviously far from perfect. But if you look closely, when they get to their shelter, you’ll see that instead of rushing to safety, Mrs Lloyd first makes sure that her husband gets there first. Now this is what I call true love! Risking your own life like this to make sure the other person is safe may not necessarily look “romantic”, but true love is not at all about feelings and looks, but about deeds. As someone who has been married for almost two decades I can assure you that nice and pleasant feelings about one’s spouse come and go (and then come and go again, and again, and again – it’s not that it’s over after a year or two, it’s just that feelings depend on many, many factors, most of them outside our control), but a decision to care for them can (and should) stay firm.

What’s more, we don’t even get to know Mrs Lloyd’s first name, not even from the script. This is sad, but for me it reinforces the notion that love is selfless and “does not seek its own interests”, as St. Paul put it in his beautiful song about love in 1 Corinthians 13.

Mrs Lloyd making sure her husband gets to safety