Main page

Welcome to my weblog about Doctor Who, where (almost) every post is devoted to analysing one episode in depth!

PSA: this weblog is no longer updated. I might write something new here if there is some interest, but please do not consider that a promise.

You can read more about this project, look for answers to frequently asked questions, contact me and support me. There is also some information about my spoiler policy and some disclaimers and legal stuff. The three most recent posts are below; you can also check the full archive or the list of covered episodes and the RSS feed.

Most recent posts:

Happy Easter for everyone! Jesus Christ died, but is back from the dead, and is stronger than death! Will you follow Him all the way to Heaven?

Also, I will offer a decade of Rosary for everyone who reads this humble weblog!

And if this Doctor should return, then he should beware, because

Torchwood will be waiting.

This time I have to plainly say this. Tooth and claw is not among

my favorite episodes at all. It’s not that I dislike it for some

specific reason – in fact, there are a few things I do like about

it, and it is actually quite hard to pinpoint why exactly it doesn’t

resonate with me – but overall it fell a bit flat for me. Still, in

line with my general attitude, I’ll try to focus on the good parts.

To me, one of the most important events in this episode is the

sacrifice of sir Robert MacLeish. I find it a bit emotional, even if

I have some problems with it.

One of these problems is that his sacrifice seems entirely

unnecessary. Granted, he probably stopped the

I committed treason for you,

That said, I would still not condemn him. The circumstances were

extremely difficult, time was scarce, and he must have been under very

strong emotions, so his actual moral responsibility must have been

diminished by these factors. It is one thing to theorize about

morality, which is a good thing to do – in fact, that’s an important

reason to engage in art, to be able to assess difficult moral

decisions in a safe and comfortable environment of one’s armchair –

and another to place the blame on people from the same comfortable

environment. Was his decisions wrong? Almost certainly. Was he to

blame for making a wrong decision? Maybe, maybe not.

Taken all this into account, another (slight) problem I have with what

sir Robert did is very mundane and not really very important… but

why did he try to fight the werewolf with a sword, of all things?

To a modern man, choosing a melee weapon and not a ranged one like

a gun seems a bit stupid. On the one hand, sir Robert clearly saw

the werewolf shot multiple times and not hurt by that – but on the

other one, the shooting did slow it down considerably, and it

retreated for a long while. Of course, the sword looks more dramatic,

but using a gun could be much more effective, even if in the end sir

Robert would die anyway. Well, Doctor Who has never been big on

logic and internal consistency…

An important theme in Tooth and claw is that the Doctor and his

companions often treat deadly dangers in a strikingly lighthearted

manner. We will see this again very clearly at the beginning of

spoiler for series 2The impossible planet and of course

in spoiler for series 9Face the raven, but this is

a topic which is hinted at many more times, for example in

spoiler for series 2The runaway bride (Donna’s “Are you enjoying

this?” moment), spoiler for series 5The time of angels

(when Father Octavian says “And when you’ve flown away in your little

blue box, I’ll explain that to their families”) or in

spoiler for series 11The woman who fell to Earth (when Grace asks, “Is

it wrong to be enjoying this?”).

It is perhaps astonishing that I tend to side with the Doctor here

a bit. Yes, there exist very serious situations. Yes, death is not

something that should be treated lightly. But that does not mean that

we should not approach even very serious topics with some sense of

humor. I think it is a wonderful gift of God we can use especially

in difficult times to deal with them more easily and with a bit less

stress – maybe even with a bit less pain. In fact, jokes and funny

comments are an important part of my own life, even if I do face

a really grave situation now and then. And I often keep in mind this

wonderful quotation from venerable Fulton J. Sheen:

However, there is a close relationship between faith and humor. […]

Materialists, humanists and atheists all take this world very

seriously because it is the only world they are ever going to have.

He who possesses faith knows that this world is not the only one, and

therefore can be regarded rather lightly: “swung as a trinket about

one’s wrist.” To an atheist gold is gold, water is water and money is

money. To a believer everything in this world is a telltale of

something else. Mountains are not to be taken seriously. They are

manifestations of the power of God; sunsets are revelations of His

beauty; even rain can be a sign of His gentle mercy.

Treasure in clay: the autobiography of Fulton J. Sheen, p. 314

So, even though I do understand Queen Victoria’s disgust – after all,

she barely escaped death, and Rose, well, was amused, I think she

definitely overreacted when exiling Rose and the Doctor. (Not that

they cared about it too much.)

She may have not been amused, but Rose – and us viewers – definitely

were.

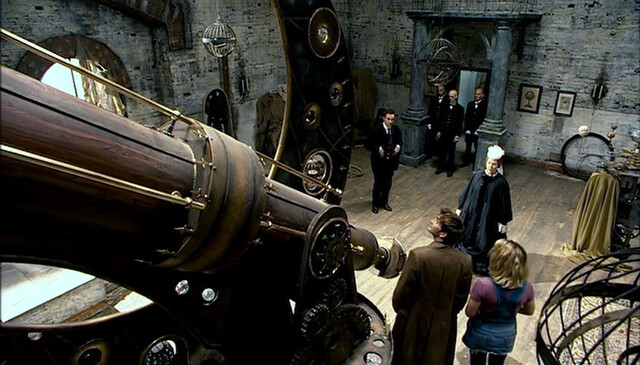

One of the best moments of Tooth and claw is the presentation of the

observatory. It starts with sir Robert being a bit emotional about

his father (which is completely understandable), becomes funny with

the Doctor “being rude again” and Rose trying to win her bet in an

embarrassingly heavy-handed way, and then turns quite unexpectedly to

philosophical with Queen Victoria’s comment.

This device surveys the infinite work of God. What could be finer?

Sir Robert's father was an example to us all. A polymath, steeped in

astronomy and sciences, yet equally well versed in folklore and

fairy tales.

And in fact, I do agree with her here. It is tempting to only

consider trivial issues like sustenance and shelter, but we humans

need to spend time on higher matters, too. Science, literature, art,

mathematics – and many others – are worth pursuing even if they cost

us a lot and gain nothing (at least in terms of immediate and tangible

profits).

This device surveys the infinite work of God.

Interestingly, the Doctor’s comment – “stars and magic” – is something

I don’t like. Of course, conflating “folklore and fairytales” with

“magic” is sort of understandable from a secular point of view, but

they sound very distinct in my Catholic ears. While studying

folklore, local legends and myths can be extremely valuable and help

us understand people and their culture better, dealing in actual magic

is a very dangerous thing. (Let us put aside the question whether

magic actually works and hence is a sin because people practicing it

are cooperating with demons, or whether magic does not work and hence

it is a sin because people practicing it are lying when they claim

they can achieve anything through it. The question is definitely

interesting, several hundred years old and deserves a discussion – but

I do not consider myself knowledgeable enough to discuss it.)

Coming back to the issue of the value of stargazing and other

“pointless” activities like arts and theoretical sciences, let me also

mention that this is something I personally sometimes struggle with.

On the one hand, there is a widespread attitude of “worse is better”,

where it is claimed that it is not economically viable to strive for

perfection in a product, since it costs too much. On the other hand,

there is a less common attitude that we should offer our work to God,

and hence perform it in the best manner we can achieve. Here is how

Saint Josemaría Escrivá put it:

It is no good offering to God something that is less perfect than our

poor human limitations permit. The work that we offer must be without

blemish and it must be done as carefully as possible, even in its

smallest details, for God will not accept shoddy workmanship.

(Friends of God, 55)

and later:

I used to enjoy climbing up the cathedral towers to get a close view

of the ornamentation at the top, a veritable lacework of stone that

must have been the result of very patient and laborious

craftsmanship. As I chatted with the young men who accompanied me

I used to point out that none of the beauty of this work could be seen

from below. To give them a material lesson in what I had been

previously explaining to them, I would say: 'This is God's work, this

is working for God! To finish your personal work perfectly, with all

the beauty and exquisite refinement of this tracery stonework.' Seeing

it, my companions would understand that all the work we had seen was

a prayer, a loving dialogue with God. The men who spent their energies

there were quite aware that no one at street level could appreciate

their efforts. Their work was for God alone. Now do you see how our

professional work can bring us close to Our Lord? Do your job as those

medieval stonemasons did theirs, and your work too will be operatio

Dei, a human work with a divine substance and finish.

(Friends of God, 65)

My problem is, if I were to “finish my personal work perfectly” every

time, I would at least get a lecture from my boss, and it would be

hard not to agree with him. It would mean that I spend time (and

hence money of my employer) on things that do not benefit them, which

by the way seems morally dubious to me, too. On the other hand,

turning in half-baked products of my work would also be wrong (and

bad). What to do, then? Frankly, I don’t have a good, universal

answer. Maybe it is just a question of experience and wisdom to know

when to stop perfecting a piece of work and decide it is good enough?

Before I move to the next topic, let me mention something slightly

more light-hearted I learned about recently. There is a small station

on one of the Japanese railways, called the Seiryu Miharashi Station,

which does not have any roads (or even paths) leading to it. In

other words, after you get off the train there, the only way you can

leave it is board the train again. The only purpose of existence of

the Seiryu Miharashi Station is as a viewing platform for the

Nishiki River. I do not know much about the Japanase culture, but

I love this example of spending a lot of money only to make it easier

for people to appreciate the beauty of nature.

Death and sacrifice is a very common topic on Doctor Who. It is not

surprising, that another death-related concept, the mercy kill,

appears in the show, too. This is an important topic – especially in

today’s world – where many people consider it acceptable to kill

someone so that they can avoid suffering. Tooth and claw is (I

think) the second episode of New Who (the first being Dalek) dealing

with that subject, but definitely not the last. Did the Doctor do

right when he essentially killed the boy who became the werewolf?

Essentially, the concept of mercy kill is fundamentally incompatible

with Catholicism – the right thing to do is to accompany a dying (and

suffering) person as best as we can, not to shorten their life.

I already mentioned the concept of not performing so-called

“over-zealous treatment”, which is very distinct from euthanasia, but

this is not the case here. Can we justify the Doctor complying with

the boy when the latter begged him to “let him go”? I gave some

thought to it, and I honestly don’t know. I think it may be

justified as legitimate defense – after all, the wolf was intent on

bringing the Empire of Wolf to the Earth, and presumably killing

many (or all) humans. Containing it could be impossible (or at least

extremely hard, without a good chance of succeeding), sending it

elsewhere would be immoral (since it would probably just wreak

destruction there), so killing it may have been the only viable option

of defending the Earth – and apparently, it could not be killed

without killing the poor boy at the same time… I don’t envy the

Doctor that choice! I just hope I’ll never face a man turned

werewolf, with the choice of killing the wolf without being able not

to kill the man!

Unlike The end of the world, the cross-like imagery here

As usual, in this section I’ll just briefly mention a few things that

caught my attention, but for this reason or another I did not discuss

them at length.

The scene with the monks fighting in an Eastern style is so utterly

absurd and ridiculous that I genuinely don’t know what to say about

it. I wonder what the thought process of the writers looked like. “–

Let’s have these Scottish monks fight like stereotypical ninjas. – Ok,

but let them be orange instead of black. – Great, but why a Christian

monk would know martial arts? It doesn’t make any sense! – You’re

writing for Doctor Who, you’re not paid for making any sense!”

And then the Doctor wants to take Rose to 1979, only ending up in 1879

instead. The subject of the T.A.R.D.I.S. “not being very reliable”

will be brought up in the future, but here’s another thing. In quite

a few episodes (first in Boom town, I think) we learn that the

T.A.R.D.I.S. is not just a mechanical device, but (at least partially)

a living creature. Does she not mind the Doctor repeatedly hitting

the console with a hammer, then? I really don’t want to get deeper

into that…

While I already said that I’m not a big fan of risqué jokes, I find

the running gag about Rose’s “nakedness” actually pretty funny. Of

course, what’s really funny is Rose trying to speak with a Scottish

accent and the Doctor (or was it David Tennant?) being, well, very

much not amused. spoiler for series 7This starts a trend continuing

with several companions of Ten, and sets up an absolutely hilarious

scene in The Rings of Akhaten where Eleven has the exact opposite

attitude.

The “I’m Doctor James McCrimmon, from the township of Balamory.” quip

seems not very funny unless you know that Jamie McCrimmon was an

actual companion of the Second Doctor, and Balamory is a fictional

place from a Scottish children tv show of the same name.

Another sentence from the Doctor – “I trained under Doctor Bell

himself” – was a little baffling for me. Initially, I assumed it was

about Alexander Graham Bell, who was indeed Scottish, but only

received a (honorary) doctorate of the University of Edinburgh

in 1906. In fact, he was only 32 in 1879. (And this, by the way,

would not be the first time that Bell is mentioned in New Who.) After

consulting the T.A.R.D.I.S. wiki, I learned that I was wrong – it was

Doctor Joseph Bell, who actually worked at the University of Edinburgh

and was an inspiration for Sherlock Holmes.

The bet Rose made with the Doctor that Queen Victoria would at some

point say that she is not amused was another great joke – made even

better by the fact that Doctor clearly lied about the reasons he

didn’t want to make that bet. Of course, Rose repeatedly trying to

make Her Majesty to say the thing – and Doctor’s being more and more

exasperated – were hilarious, too.

The “Am I being rude again?” quip from the Doctor was a great callback

to The Christmas invasion. Such little nods to past episodes are

among my favorite parts of the show, and it does deliver on that

front.

Speaking of callbacks, it’s hard not to mention Rose remembering to

ask Flora her name. Time and time again she shows that she cares

about people, and asking them their names is a very good way of

showing that. In fact, names are a big deal in Doctor Who, and I’m

all for it – being steeped in Biblical tradition, I love when various

works of art take up this subject.

Frankly, after Rose asked Flora her name and almost promised her

safety,

I also liked the moment when Rose said about the werewolf that “He's

a prisoner. He’s the same as us”. Again, it showed her compassion.

Here was what was basically a monster to lady Isobel and other

captives – but Rose sees that he is enslaved, like them, and felt

compassion for him, too. (The fact that the werewolf – or the lupine

wavelength haemovariform, if you like – broke out of the cage with

ease is irrelevant here, since Rose couldn’t have known that.) There

is actually a deeper spiritual meaning behind this. In

a villain-and-victim scenario, they are in fact always both victims.

Every perpetrator harms primarily themselves – yes, they can kill the

[victim’s] body, but in doing that, they are destroying [their own]

soul, (compare Matthew 10:28). Obviously, this does not negate the

fact that the victim deserves compassion and help, and that justice

demands that the perpetartor is punished – but it does mean that the

perpetartor needs compassion, too, even if they might not deserve

it. (And frankly, I wouldn’t be sure about them not deserving it,

either. This is a difficult topic, and I really hope to get back to

it – this tends to come up in Doctor Who quite a few times, for

example in spoiler for series 4Partners in Crime,

spoiler for series 4The next Doctor,

spoiler for series 5The vampires of Venice,

spoiler for series 5Vincent and the Doctor,

spoiler for series 6The rebel flesh/The almost people,

spoiler for series 6The God complex,

spoiler for series 7The bells of Saint John,

spoiler for series 7Time heist,

spoiler for series 8Mummy on the Orient Express,

spoiler for series 9The Zygon invasion/The Zygon

inversion – but probably most notably in

spoiler for series 7A town called Mercy.

And speaking of the werewolf, the whole exchange between him and Rose

is really good. From his “oh! intelligence!” to the mention of Bad

Wolf, the whole scene is great. Not to mention the transformation

itself, which looks really cool – you can tell that Doctor Who went

a pretty long way since burping trash cans as far as the special

effects go.

One of my favorite parts of the episode is the story of lady Isobel

and her husband sir Robert. We don’t get too much of a backstory

here, but what we can see from a few glimpses is really compelling: he

is an honorable man, she is a resourceful woman, and what is most

important, you can see how they love each other. I have a strong

suspicion that their kiss in public was not something that would

actually happen in Victorian times (though what do I know?), but you

know what? I don’t care at all. As a married person myself, I love

it when movies or tv shows have happy marriages. And I also like the

fact that it’s important to sir Robert that his wife “will remember

him with honour” – and though it is not mentioned explicitly, my

personal headcanon is that she, in fact, did. It is yet another very

subtle reminder that love transcends death.

One very minor tidbit I loved was that even when their leader was

killed, the “brethren” just continued to work. This is a mark of

a good organization, and villains or not, their competence must be

applauded. I’ve seen many times a scenario when a visionary leader

would start something great, and then after they die (or just get

bored, or change jobs, or leave the project what whatever reasons),

there is nobody to step into the role and the project crumbles. (I

have to admit that I even was that leader once or twice – on a very

small scale, of course, and I didn’t die, of course, just went on –

but the mechanism stays the same.)

As a chronic bookworm, I cannot not love when the Doctor exclaims:

“Books! Best weapons in the world.” This, in fact, is very true –

while swords and guns can win battles and even wars, ideas are what

wins in the long term. (History of the Church is an obvious example,

but far from the only one. There are quite a few examples of

civilizations conquering other civilizations only to absorb their

ideas – language, beliefs, way of living.)

It was interesting to hear Queen Victoria say “I would destroy myself

rather than let that creature infect me”. While understandable, it

obviously makes me feel a bit uneasy – after all, killing oneself on

purpose, a.k.a. suicide, is something that should not be taken

lightly. As I have already mentioned twice on this weblog, this is

another very difficult subject. I would presume that if you were

a powerful monarch and a target of a werewolf-slash-alien evil

creature who wants to install itself in your body to take your power

and use it to destroy the Earth, you could be morally justified in

killing yourself in order to avoid that, but I would not be surprised

to hear some argument countering that.

I also noticed Her Majesty describe the Koh-i-Noor as “the spoils of

war”. I am no history expert, but I think that could be said about

quite a few things in Great Britain. I am definitely not competent

enough to discuss this, but the question of what and how should be

restored after taken by force after various conflicts seems an

important one. (Well, as a citizen of a country which was much more

often on the receiving end of various wars than an aggressor – in

fact, that happened maybe once, maybe twice in our history – I’d

naturally like some justice here – but I don’t hold my breath…)

And right after bringing up this heavy subject, we have a lovely piece

of black humor from the Doctor – when the Queen says about the diamond

that “it is said that whoever owns it must surely die”, he points out

that “that's true of anything if you wait long enough”. It was hard

not to laugh at this one! Of course, Doctor and Rose commenting on

what might happen if Jackie was there was also pretty funny.

Another thing I absolutely loved is the scene of sir Robert’s death.

In a blink-or-you’ll-miss-it moment we can see the Queen clutching

a small cross and praying. This, my friends, is one of the best

possible reactions when you see (or hear) someone die and you can’t do

anything about it.

And of course, in the final moments of the episode, Queen Victoria

banishes Doctor and Rose and says, “your world is steeped in terror

and blasphemy and death, and I will not allow it. […] you will

reflect, I hope, on how you came to stray so far from all that is

good, and how much longer you may survive this terrible life”. Seeing

Rose laughing at the idea that the royal family might be werewolves

just a few minutes later makes one think that Her Majesty was not

entirely wrong…

Finally, there are some absolutely fantastic pieces of trivia

related to this episode. For example, it gave the actress Pauline

Collins a record for the longest interval between appearances on

Doctor Who – she played a certain Samantha Briggs in the Second

Doctor’s story The faceless ones, aired in 1967, and Tooth and

claw, where she played Queen Victoria, aired in 2006. (This record

was broken a few years later by Arthur Cox.) Also, I read that

mistletoe is not something you’d naturally encounter in Scotland,

which means that sir Robert’s father must have imported it on purpose

to guard the house against the werewolf. And finally, this episode

has a very nice callback to World War III, where Jackie Tyler

commented that Rose should be knighted.

Now, this article is already much longer than I expected, especially

given that Tooth and claw is not one of my favorite episodes. But

there is one last thing I have to mention. When the company sit

down and eat, we get this beautiful little speech by Queen Victoria

about ghost stories.

And that's the charm of a ghost story, isn't it? Not the scares and

chills, that's just for children, but the hope of some contact with

the great beyond. We all want some message from that place. It's the

Creator's greatest mystery that we're allowed no such consolation.

The dead stay silent, and we must wait.

Queen Victoria contradicting herself, since prayer for the dead

And you know what? I said it was beautiful, yes, but not that it was

true – since it’s not. The dead do not stay silent, since there was

one Man who died and then came back to tell us “Peace be with you.”

If that is not a consolation, I have no idea what is!

– So where are we going?

I really shouldn’t like this episode – yet somehow it works for me. I

guess I just really want to like Doctor Who (and who can blame me

for this?), and go out of my way to redeem even weaker episodes. So,

let me be fair first and briefly state why this episode is not the

best one, and then I’m going to look for some good stuff.

There are perhaps two and a half reasons New Earth is far from my

favorite episode. If you are a regular reader of this weblog, you

will probably guess that making members of a religious order the main

villains is a sure way to irritate me. Perhaps surprisingly, I

actually don’t have a big problem with that. I have lived long enough

and I know enough history to understand that being a nun, a priest, a

bishop or even a pope doesn’t automatically make you saint. (That

said, treating clergy’s sins as an excuse for one’s own is one of the

most stupid things people ever came up with – but this is of course

not what New Earth is about.) Well, I am a very religious person

myself (even though I’m a layman), and I’m painfully aware that I’m a

sinner whose only hope of redemption is God – and the same goes for

every other living person. So, evil cat-nuns are sadly not that far

from reality as one might think (well, maybe apart from the “cat”

part;-)), though watching people who should live up to their ideals

doing evil is of course a bit disturbing. (Although Novice Hame is

actually quite nice.)

“Who needs arms when we have claws?”

What problems do I have then with New Earth? First of all, Doctor

Who is a family show, and watching it with kids is something I

appreciate a lot. While I don’t have a problem with one or two

innuendos which would fly over children’s heads anyway, the density of

almost explicit sexual jokes in this episode makes me cringe. Too

much is just too much. (Also, one of these jokes perpetuates certain

annoying and even harmful misconception – but I’ll get to that later.)

Another reason New Earth bugs me is that the Doctor is clearly very

much enjoying his “god mode”. Nine was much more humble and aware of

his shortcomings. It is rather telling that even at his very start,

Ten is quite the opposite. spoiler for series 4This, of course, will

culminate in The waters of Mars and The end of

time. It’s most prominent when he blurts to Novice

Hame, “if you want to take it to a higher authority, then there isn’t

one. It stops with me.” It is actually a very well-written line,

showing the vanity of the Doctor, and the fact that it makes me cringe

is a testament to that – but it still does. Another moment when the

Doctor’s god-like attitude is very visible is near the end, when he

cures the patients. He is (probably intentionally) shown as a

priestly figure, and it is interesting to compare him to the cat-nuns.

While they are obviously the villains in this story, they do have

some justification for their actions (that is not to say that I agree

with said justification, of course!), and they – especially Novice

Hame – seem to show a true sense of service and humility. The Doctor,

on the other hand, is (again) full of pride – “I’m the Doctor, and I

cured them!”. He really cares for Rose (obviously), for the “new

humans” (which is also very typical of him) and even for Cassandra

(which is perhaps a bit less obvious, but true nonetheless), but his

conceit is really hard to stand. (One might argue that this line

doesn’t show the pride of Ten but his genuine joy, almost like the

famous “everybody lives” moment. I can certainly agree that there is

a component of joy here, but he didn’t say “Look Cassandra, they are

healthy now!” or anything like that – he did emphasize that he was

the one who cured them.)

The third issue I have with New Earth is a bit nitpicky, but I’ll

mention it anyway. Being a Whovian, I completely understand that

expecting any sort of logic or scientific accuracy from Doctor Who

is absurd, but the main premise of this episode is really egregious.

The idea that you can cure terminally ill people by dousing them with

intravenous solutions doesn’t make any sense whatsoever. And there

are more questions! Now that the farm of “new humans” is gone, how

will the hospital operate? Won’t there be a global pandemic there

very soon? (spoiler for series 3Well, in fact there will, thirty years

later, although not a “natural” one.) But of course,

let’s not be too pedantic – after all, this is Doctor Who, not a

book by Stanisław Lem.

Probably the main strength of New Earth is comedy. This is one of

those light-hearted episodes where you don’t really expect too much

drama or thriller elements – you just have some silly fun. Granted,

there are serious moments here – more about them in a moment – but

this is neither Father’s Day nor spoiler for series 4The fires of

Pompeii. As I already mentioned, I’m not really a

great fan of the density of sexual jokes in this episode (even if I

admit that some of them are actually pretty funny) – but there’s more

to it than them. I love the elevator scene (“watch out for the

disinfectant!”) – this will certainly make my top ten funniest moments

of Series 2. The Doctor’s comment about the lack of the little shop

is also something to be appreciated (spoiler for series 3and it will

make a return in about a dozen episodes,

spoiler for series 4and then even later in the Library!).

And of course, the “New New New New New New New New New New New New

New New York” scene is, to borrow Nine’s favorite phrase, absolutely

fantastic.

“Watch out for the disinfectant!”

On the other hand, there are a few very serious moments scattered

throughout New Earth. And maybe just because they are very few and

very short, their impact is even greater. The scene where Cassandra

experiences the terrible loneliness of one of the infected is probably

the most pronounced, but definitely not the only one. I love the

Doctor telling the cat-nuns, “and I'm being very, very calm. You want

to be aware of that. Very, very calm.” This definitely sends chills

down my spine, especially knowing what the Doctor is capable of.

We’ll get similar vibes very soon in spoiler for series 2School

Reunion, much later in spoiler for series 3The family

of blood and in many other episodes. The moment when

a normally hyperactive person starts to act unnaturally composed is

something very real, and the threat hidden in Doctor’s voice is really

well acted. And of course we have the Face of Boe, who is supposed to

tell the Doctor his “great secret” but for some mysterious reason

changes his mind. (That reason will be easy to explain after

spoiler for series 3the next series’ finale, though.)

Having experienced caring for a terminally ill person myself, I may

have shed a tear or two when Novice Hame discussed the situation of

Face of Boe with the Doctor. It’s a pity that this aspect wasn’t

expanded just a bit – it would be a great lesson to teach the younger

part of the audience.

Now, let me get more serious myself. I’m normally a very positive

person, and if you’ve read even a few articles on this weblog, you are

well aware that I try really hard to find good things to say even

about the weaker episodes. (spoiler for series 2Just you wait till we

get closer to the end of this series!) That doesn’t

mean, however, that I don’t see their worse aspects. Sometimes I just

have to call attention to them, not only because they irritate me,

but more because they teach a wrong lesson. (Remember that cringey

remark about Marxism in The empty child?)

Chip sees to Cassandra’s physical needs. Basically, he moisturizes her.

Here we have a similar (even if much less visible) situation. One of

the attempts at humor by Russell T. Davies (and we all know that he

likes jokes aimed at the… less mature part of the audience) was

Cassandra’s remark about how “Chip sees to [her] physical needs”, to

which Rose dryly responds “I hope that means food”. You may ask, why

I don’t like it? There is a very subtle thing going on here. It is

fairly obvious what Rose thinks the “physical needs” are, and

chances are she is right. And here comes the misconception I

mentioned earlier. Contrary to the popular opinion, sex is not just

a “physical” thing. It is a very deep experience touching all aspects

of humanity – it has its physical component (obviously), but it has

also profound psychical and even spiritual aspects. I’m neither a

theologian nor a sexologist, so I won’t try and pretend that I know a

lot about these topics, but I’m a husband and a father, so I do know

at least a bit from my personal experience. These quotes from the

Catechism (CCC 2360–2363, but the whole chapter is well worth studying

even if you’re not a Catholic, if not to admire the beauty therein,

then at least to understand some of our perhaps less popular beliefs)

sum it up much better than I could.

Sexuality is ordered to the conjugal love of man and woman. In

marriage the physical intimacy of the spouses becomes a sign and

pledge of spiritual communion. Marriage bonds between baptized persons

are sanctified by the sacrament.

Sexuality […] is not something simply biological, but concerns the

innermost being of the human person as such. It is realized in a

truly human way only if it is an integral part of the love by which a

man and woman commit themselves totally to one another until death.

The acts in marriage by which the intimate and chaste union of the

spouses takes place are noble and honorable; the truly human

performance of these acts fosters the self-giving they signify and

enriches the spouses in joy and gratitude.

The spouses’ union achieves the twofold end of marriage: the good of

the spouses themselves and the transmission of life.

So, do not try to tell me that sexual desire is a “physical need”. It

is much, much richer and more beautiful than that!

Before I get to my main point about New Earth, let me – as usual –

mention in passing several minor things that caught my attention.

I quite like the very first few seconds of the episode when Ten

manipulates the T.A.R.D.I.S. However, we then cut to the good-bye

scene with Jackie and Mickey, which is full of cringe – especially the

moment when Mickey says “I love you” to Rose, and she answers just

“bye”. Poor Mickey.

“You’re hard work young!” (spoiler for series 4Professor River

Song)

I love the exchange about the name of New New York, the city “so good

they named it twice”. (Though I’m not sure New York is really a good

place.) Also, Rose hopping and commenting on “different ground

beneath [her] feet” is incredibly cute. The nostalgia and the “big

revival movement” sound so close and so human to me… I’m a bit

nostalgic person myself and I fully understand that – even though I am

aware that you can’t really go backwards in time to the “good old

days” of your childhood – yet still I like memories and things that

remind me of them.

Also, as a mathematician, I cannot not smile at the subtle joke about

numbers. See, thirteen episodes ago Nine said that “five billion

years in your future […] is the day the Sun expands”. When we say

or hear things like that, we obviously understand that “five billions”

is a very rough approximation – it could well be off by a thousand (or

a million) years. Here, however, it is implied that the world ended

exactly in the year 5,000,000,000, since New Earth is set in the

year 5,000,000,023, two decades later. Interestingly, all these

calculations are off anyway, since technically “five billion years in

the future” during the events of The end of the world would be

5,000,002,005. Also, year five billion being called 5.5/Apple/26 in

the future means that the future calendar in the Whoniverse is most

probably no longer based on the date of birth of Jesus, which is not

surprising given RTD’s views. And while we’re at anti-religious

sentiments of RTD, substituting the red cross with the green moon

seems to be yet another case of that. When I think about it, New

Earth seems to be one of the most anti-Christian episodes of

Series 2. Funny how its main message – which we’ll get to in a few

minutes – is so in line with Catholic teaching and against the popular

beliefs of today! I cannot not think of John 11:49-52 and the story

of Caiaphas, who wanted to get rid of Jesus, but inadvertently said a

prophesy…

The Doctor also mentions that they are in galaxy M87. This is a real

one, and Wikipedia told me that it is pretty far from Earth – some 53

million light-years. This means that either humans will have invented

FTL travel by the year 5,000,000,023, or they just started much

earlier and took their time to get there, or they had some other means

of traveling such vast distances. (In fact, all three possibilities

may be correct. spoiler for series 4The waters of Mars establishes

that humanity sent their first lightspeed ship to Proxima Centauri in

2088, and spoiler for series 2in The girl in the fireplace

the Doctor, Rose and Mickey will visit a 51-century spaceship

utilizing warp engines.)

I keep thinking whether the rule that “cuttings from the gardens are

not permitted” is a subtle allusion to Jabe’s gift.

I like the short exchange about illnesses, where Rose says, “I thought

this far in the future, they’d have cured everything”, to which the

Doctor replies, “The human race moves on, but so do the viruses. It’s

an ongoing war”. It reminds me of sentiments of “progress”, as if

humanity was just marching forward and becoming better and better.

Sadly, it does not work this way. (Well, in certain areas it does.

When it comes to scientific and engineering knowledge, for example, we

basically build upon what we already have, so the sum of that type of

knowledge is more or less steadily increasing – even if some of it is

lost for various reasons. But unfortunately humanity does not always

progress morally. Our own times seem to be a deep regression in quite

a few pretty fundamental aspects, for example.) And speaking of

progress, there’s yet another moment which seems a jab at

conservatists, when Rose has this to say to Cassandra: “You stayed

still. You got yourself all pickled and preserved, and what good did

it do you?”. Well, my personal stance is that conservatism (and I

think I would call myself conservative) is not about trying to avoid

any change, but rather about believing that change for change’s sake

is not really valuable, and that (as I said a moment ago) not every

change in our society is necessarily for the better – and many are

definitely for worse. (Also, whenever you want to change something,

you should really consider if you aren’t accidentally demolishing a

Chesterton fence!)

Much like in Series 1, the “futuristic” look of the hospital says more

about 2005 than about the future. And even though the hospital looks

(a bit) futuristic, the lift exterior certainly does not. One would

think that lift technology a billion(ish) years in the future wouldn’t

look exactly the same…

I have to say that I have rather mixed feelings about Frau Clovis. On

the one hand, as her name suggests, she couldn’t be more stereotypical

German lady, which is funny indeed. On the other hand, jokes

utilizing stereotypes like this are a bit risky. (On yet another

hand, we live in very strange times, where simply stating your own

opinions on general, non-personal matters seems to offend some people,

so going to great lengths not to offend anyone is futile anyway, and

I don’t think her character is really offensive to Germans –

especially that she doesn’t actually do anything bad.)

I absolutely love the fact that the Doctor remembers the Face of Boe,

even if that’s not surprising at all. It is even better that Rose

seemed to remember Lady Cassandra well enough to recognize her voice

on the film! It shows that they are both very attentive to the people

around them, and that’s really great. On the other hand, Rose’s

rather snarky remark about Chip (calling him “Gollum”) is funny, but

not exactly respectful, so there’s that. Even taking that into

account, the contrast with Cassandra, who accuses Rose of murder

(well, when she says “you murdered me”, she might have meant both of

them, Rose and the Doctor, but still) despite the fact that Rose was

the one to plead with the Doctor to save her on Platform One.

I have to admit that I quite like Novice Hame, and the scene when she

talks with the Doctor about the Face of Boe is particularly good. I

can’t help but giggle, though, when she says “I can hear him singing,

sometimes, in my mind. Such ancient songs…” – my personal headcanon

is that one of those “ancient songs” is a certain “traditional Earth

ballad”;-).

New Earth is the first episode when Ten says “I’m sorry, I’m so

sorry”, which we’ll hear many, many more times during his tenure.

Matron Casp saying (with a hint of amazement), “fascinating, it's

actually constructing an argument”, as if that should be one of the

moments convincing the audience that the “patients” are actual humans,

aged rather poorly now that “constructing an argument” became somewhat

cheaper due to the spread of LLMs. This, however, reminds me of a

very important truth: humanity does not depend on intelligence. You

don’t need to be able to “construct an argument”, speak language, or,

say, perform algebraical operations to be considered human and to have

rights as a human being. (And apparently it is possible for

non-humans to “construct an argument”, although it seems that LLMs are

not really “constructing an argument”, they just generate a stream of

letters and words which sometimes look reasonable.)

Interestingly, this episode was the first one of New Who which did

not take place on or near Earth. From now on, every series will have

at least one episode happening in space or on another planet, but Nine

and Rose never went further (in space) than to the Earth’s orbit.

The last two things I'd like to mention here are more about the

filming process than the episode itself. Firstly, it's not easy to

spot it because of the heavy makeup, but Sister Jatt was played by

Adjoa Andoh, who will go on to play spoiler for series 3Francine Jones,

Martha’s mother, in the next series. And secondly, the

"intensive care" scenes were filmed at the Ely Paper Mill in Cardiff,

which served as the Nestene base in Rose and will be visible in quite

a few more episodes of series 2 and 3. (It would probably be used

more if not for the fact that it has been demolished 15 years ago.)

It is perhaps surprising that they main topic of this rather

lighthearted episode is something very, very serious. As with many

other episodes of Doctor Who, this one is mainly about life and how

we should respect it, even if it’s life in a form we are not fully

comfortable with. I don’t know how other people interpret New

Earth, but for me, the story of the “flesh” (interestingly, the same

term will be used to describe apparently unrelated creatures in

spoiler for series 6The rebel flesh and

spoiler for series 6The almost people, but that

two-parter can be interpreted in a quite similar way) is a very clear

metaphor for people conceived using the IVF technique.

First of all, even if they are “artificially grown” (a tiny bit like

in the case of IVF, though obviously the analogy breaks here), they

are obviously humans – even if some people may not treat them as such.

That should go without saying – although the common practice seem to

show that it sadly does not. As far as I know, more embryos than

necessary are usually conceived during an IVF procedure, which means

that several persons start to exist – but are either “destroyed” (in

other words, killed) or “frozen indefinitely” (which most likely means

they will be killed in the future anyway, probably depending on

economic factors). It’s not really different than Matron Casp

casually ordering Sister Jatt to incinerate one of the “patients” – of

course, in that scene the humanity of him was reinforced by his

ability to talk, but from the moral standpoint, the situation is

basically the same.

On the other hand, I would not dare to accuse parents of children

conceived via IVF of murder – I have a very strong suspicion than very

many of them are not fully aware of what is really happening. As

Novice Hame puts it, “think of those humans out there, healthy and

happy” – and indeed they are, oblivious of the inhumane process that

made them happy. On the other hand, what Doctor says in response (“if

they live because of this, then life is worthless”), is very, very,

very wrong. To keep using the metaphor, neither the lives of

children conceived using IVF, nor the lives of their parents are

“worthless”, even if a grave evil was committed. Similarly, even if

we treat the story of New Earth literally, you can’t say that the

lives of inhabitants of New Earth is “worthless” – even if they were

aware of what is going on underground. Nobody’s life is “worthless”,

and every person has a great value, which does not depend on the

morality of whatever they do. According to Isaiah, this is what God

says to you and me: “Because you are precious in my eyes and honored,

and I love you” (Isaiah 43:4a) – and I think that this is true

irrespective of whatever evil anyone could commit. Just one more

Bible quotation confirming that is Romans 5:8: “but God proves his

love for us in that while we were still sinners Christ died for us”.

The most charitable way I can think of to interpret the Doctor’s words

is that he is intentionally exaggerating to shake Novice Hame up

(which is probably not a great idea anyway). The more probable theory

is that he usurps God’s authority (again!), which (as I already

mentioned a few times) is a common theme in Doctor Who, and

especially during the Tenth Doctor’s tenure. This seems to be

confirmed by his very next sentence (which I already mentioned

earlier): “I’m the Doctor. And if you don’t like it, if you want to

take it to a higher authority, then there isn’t one. It stops with

me!”, which he says very angrily to the completely justified and

sensible question of Novice Hame (“who are you to decide that?”). By

the way, Hame herself calls him “the lonely god” in an earlier scene

with the Face of Boe, although not directly.

To sum it up, if my interpretation is correct, then neither the

Sisterhood’s attitude nor the Doctor’s is the right one. Somehow I

have the suspicion that nobody saying the most reasonable thing – that

what’s going on in the “intensive care” is unacceptable, but that does

not make the humans above ground monsters whose lives are somehow less

precious – may be connected with the fact that Rose is absent from

most of the episode…

“And don’t patronise me because people have died, and I’m not happy.”

Before I finish, let me mention one more scene, very much in line of

the “lonely god” interpretation of the Doctor’s character. One can

argue (and in fact people do) that when the Doctor cures all the

“patients”, he seems to be a Christ-like figure. That is true to some

extent, but I don’t like this analogy because it doesn’t really work

that well. The reason is simple – Christ actually died for us, and

the Doctor risked much less. (Although I can imagine someone arguing

that regeneration can be viewed as a distant parallel of resurrection,

and I can see that point – but that is another topic which I might

expand, well, closer to spoiler for series 4The end of

time – pun fully intended;-).

Easter 2025

Tooth and claw

The sacrifice of sir Robert

werewolf lupine

wavelength haemovariform for a few seconds, and maybe – just maybe –

these few seconds were exactly what was needed for the Doctor to

manage to set up the telescope light chamber. On the other hand, he

may have treated it as a kind of “penance” for his earlier betrayal –

it probably makes sense for him to consider himself unworthy of living

because of that, and then he decides to punish himself by attacking

the werewolf (knowing that he wouldn’t survive that). I like that

theory even if I think that he didn’t have the right to do that.

The subject of capital punishment is an extremely delicate one, and

I am by no means an expert on it, but I am fairly sure that even if

you consider death penalty acceptable in certain circumstances, it

must follow a thorough and fair trial. It is quite obvious to me that

the old Roman rule that nemo est judex in re sua – “no one can judge

their own case” – applies here. Interestingly, it is usually

understood that any person will gravitate toward a bias favoring

themselves, not the other way round – but people are often biased

against themselves for various reasons. I know virtually nothing

about English law from the Victorian times, but it is entirely

plausible to me that an actual judge would not decide to punish sir

Robert by death, given all circumstances. On the other hand, I can

also imagine a completely different line of reasoning – that sir

Robert died a honorable death he didn’t deserve, according to the

contemporary law and moral standards (which both could well be wrong,

but that’s beside the point). Either way, him deciding himself when

and how to end his own life was wrong, period.

but now my wife will remember me with honour!

Doctor and Rose joking

The value of stargazing

And it’s very pretty, even if a bit rubbish, according to some.

Mercy killing?

does not seem to make much sense.

Other tidbits

it was rather astonishing that the girl survived until the end of the

episode…

Last but not least

is actually a form of contact with them – through God

New Earth

– Further than we've ever gone before.

Why New Earth is not entirely my cup of tea

Good laugh and a few tears

Cassandra’s physical needs

Other tidbits

Young David Tennant driving the T.A.R.D.I.S. – not a sight to forget!

Last but not least - who are new humans?

– oh, wait…